Fungi make up a remarkable group of organisms. They have a wide range of abilities which need not be detailed here. The fungi likely to be found on the Nature Reserve live on - they rot down - the dead organic matter remains of green plants as leaves or wood (and dead animals too), assisted by worms and other forms of animal life. Perhaps fortunately, the main working parts of all fungi are invisible: they are microscopic threads, mostly underground or inside the wood. But even fungi need to get out and about when it is time for sex and reproduction. The sex organs and resulting spores (acting as seeds) are still microscopic but they are produced in open-to-the-air solid bodies known as 'fruiting bodies' that we can see, possibly delight in, conceivably eat but not without guidance.

Fungi make up a remarkable group of organisms. They have a wide range of abilities which need not be detailed here. The fungi likely to be found on the Nature Reserve live on - they rot down - the dead organic matter remains of green plants as leaves or wood (and dead animals too), assisted by worms and other forms of animal life. Perhaps fortunately, the main working parts of all fungi are invisible: they are microscopic threads, mostly underground or inside the wood. But even fungi need to get out and about when it is time for sex and reproduction. The sex organs and resulting spores (acting as seeds) are still microscopic but they are produced in open-to-the-air solid bodies known as 'fruiting bodies' that we can see, possibly delight in, conceivably eat but not without guidance. No matter how solid any dead tree may appear to be there may well be fungus threads already exploring its innards. And not just one, so in course of time there can be several types of fruiting bodies on any one corpse. The fungi use up the very material of the wood (they have the necessary digestive mechanisms to do so) eventually weakening it enough for gravity to take over.

No matter how solid any dead tree may appear to be there may well be fungus threads already exploring its innards. And not just one, so in course of time there can be several types of fruiting bodies on any one corpse. The fungi use up the very material of the wood (they have the necessary digestive mechanisms to do so) eventually weakening it enough for gravity to take over.[An aside: When bread comes out of the oven it is completely dead and sterile. But leave a slice lying about and it will quickly go mouldy, because fungus spores are everywhere, all the time, in the air, on every surface, ...]

As the heading shows, fungi come in a variety of shapes and colours, mostly erupting at particular seasons of the year: it may be more than coincidence that very many fungi produce spores in the autumn when dead leaves have just been delivered. In trying to track down what's what the first useful question is, "What shape is it?". Bear in mind that some fruiting bodies change shape as they develop, mature and wither away: look around for other examples that seem to be similar but different. And if there are many similar bodies all crowded together try to discover what a single individual would look like. Then these links should be useful:

• Umbrella with a stalk and a top of some sort.

• Ball or cap with little or no stalk.

• Open cup with or without something held in it.

• Soft structure stuck sideways usually on old wood.

• Firm bracket stuck sideways, hard and roughly horizontal.

• None of the above: coating; jelly splodge; streaks; ...

UMBRELLA

The conventional 'mushroom' or 'toadstool' consists of a slightly spongy mass of fungus threads apparently growing out of the ground, out of some old wood, or, believe it or not, on a much smaller scale, out of a dead insect! But whereas familiar plants start with a seed which pushes roots down into the soil, mushrooms start as a mass of microscopic threads in the soil or whatever pushing up into the light and air. It may first appear as a modest dome (like cap mushrooms in the supermarket) which over a matter of hours or days extends upwards on a stalk, perhaps quite thick and squat or it may become tall and thin. On top is a horizontal or perhaps tubular structure which may start off as a sealed unit, in which case a covering on the underside will then rupture or peel away. The top surface is usually intended to remain intact, but may well be invaded by small forms of animal life who see it as food source.The underside of the cap contains the working parts, most commonly in the form of vertical gills radiating from the centre, as near parallel to each other as the circular geometry of the cap allows. Microscopic spores are produced in vast numbers on both surfaces of each gill: they drop down and being so minute are carried by the lightest of breezes into the general environment. Toadstools that don't have gills have a more solid-looking under-surface, with pores from which the spores are released.

| Imagine a fungus newly arrived (as a wind-blown spore) to feed on organic matter in the soil. It will soon use up the food available in the patch where it first landed, so it will spread out. But unlike a tree, say, or a creeping grass like couch grass, there will be no point in the fungus leaving its own material behind: more like an animal, the fungus will consist only of its active parts. So as it grows and expands it will continually send new threads into the unexplored periphery ahead, ignoring the exhausted central areas which it is abandoning. The result is a hollow circular growth pattern. When the time comes for it to form its reproductive mushrooms they will appear along the line of the active circle, a formation traditionally called a 'fairy ring'. The one illustrated, in the winter beechwood, was rather too wide to show clearly in a single photograph. |

|

Fairy Ring Champignon

Fairy Ring ChampignonMarasmius oreades

August

One of several groups that emerged simultaneously along the grass edging the path along the dam.

Blackening russula

Blackening russulaRussula nigricans

August - September

Modest in size and in disguising itself among the late summer beechmast. Evidently a food source for some creatures.

Giant polypore

Giant polyporeMeripilus giganteus

August - September

A huge mass of overlapping soft brackets developing in a matter of days adjacent to the stump of a felled beech tree. The bulkiest section, in the centre picture, measured 27" x 33" and was 23" tall (68 x 84 cms, 58 cms tall).

Parasol mushroom

Parasol mushroomMacrolepiota procera

August

A large single specimen, nine inches or so across and nearly a foot tall, below a young beech in a beech / scots pine area.

Rosy bonnet

Rosy bonnetMycena rosea

October

Amongst the sparse woodland flora below mixed beech and oak. Not always this colour, which seems to have attracted creatures to eat it (despite being poisonous to humans).

Shaggy parasol

Shaggy parasolChlorophyllum (Macrolepiota) rhacodes

October

Among the ivy on the oakwood floor.

Fly agaric

Fly agaricAmanita muscaria

October

This is the traditional seat of elves and pixies. Its poison made it useful in past ages as a fly killer, hence the name.

Spring brittlestem

Spring brittlestemPsathyrella spadiceogrisea

October

The photo was taken in a path-side area which had earlier been strimmed. There was quite a profusion of these delicate toadstools. You have to look carefully to spot the long, thin stalks.

Sulphur tuft

Sulphur tuftHypholoma fasciculare

October

A common fungus which seems to thrive on willow, oak and other tree species, both on the dead timber and on the ground around, always in dense overlapping tufts.

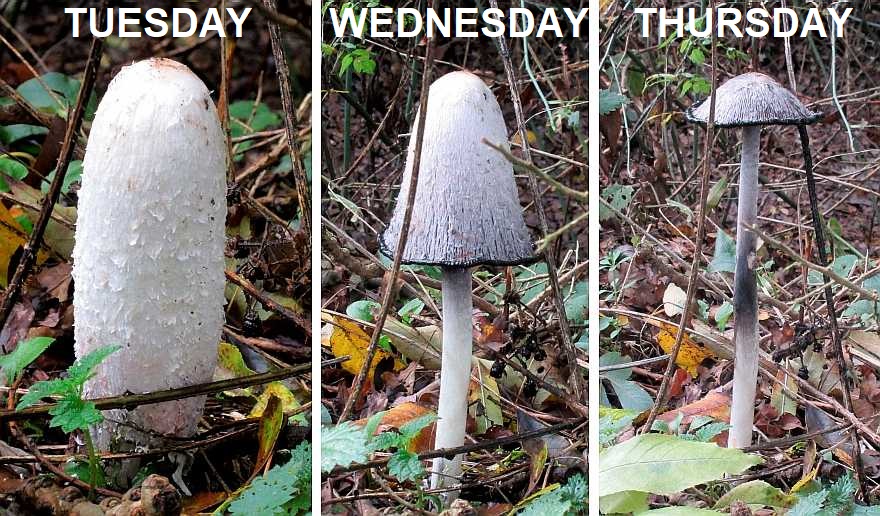

Shaggy ink cap

Shaggy ink capCoprinus comatus

October

Like other ink caps, the 'skirt' of the cap seems to melt away as drops of black ink over the course of a few days, leaving a dirty cap sitting atop a grey/white stalk until that too disappears. It can be found in many situations, grassland as well as woodland.

Common bonnet / Bonnet bell cap

Common bonnet / Bonnet bell capMycena galericulata

October

On a tree stump - as usual!

Honey fungus

Honey fungusA species of Armillaria

October

Note the button-shaped young ones too. Armillaria species are mostly parasitic on trees, which they possibly kill as a result, rapidly or over several years and still leaving the fungus active in the soil. A honey fungus infection in the Blue Mountains of Oregon, USA, is thought to be the largest living organism on the planet, its underground 'rhizomorphs' (like a network of bootlaces) measuring 2.4 miles (3.8 km) across! So far as Mill Green Nature Reserve is concerned, the infection is a significant but not overwhelming part of the balance of nature.

But honey fungus can be a commercially devastating disease of Betula (birch), Cedars, Cotoneaster, Cupressocyparis (Leylandii), Forsythia, Hydrangea, Ligustrum (privet), Malus (apples and crabapples), Peonies, Prunus (apricots, cherries, peaches and plums), Rhododendrons; Azaleas, Ribes (Currants), Roses, Salix (Willow), Syringa (Lilac), Viburnum, and Wisteria.

Clouded agaric / Clouded funnel

Clouded agaric / Clouded funnelClitocybe nebularis

October

Another beechwood floor organism.

Rooting shank mushroom

Rooting shank mushroomXerula radicata

November

A modest, hard to spot item on the beechwood floor among the autumn leaves.

Clustered brittlestem

Clustered brittlestemPsathyrella multipedata

December

A woodland fungus, in beech in this case. Apparently all those mushrooms in each group grow from one base in the soil.

Butter cap

Butter capRhodocollybia butyracea (Collybia butyracea)

December

In common with some other mushrooms, older specimeens turn up their edges. Until then their colour hid them against the background of fallen beech leaves.

Christmas mystery

Christmas mysteryIdentify, please

December

These miniature toadstools were photographed (with difficulty) on Christmas Eve, 2017. They were thriving within the texture of the bark of just a few mature, apparently healthy oaks and willows. They lasted just a few days.

Glistening inkcap

Glistening inkcapCoprinellus micaceus

January

Beech undergrowth. Like other inkcaps, the parasol edges dissolve away in the form of 'ink'.

St George's mushroom

St George's mushroomCalocybe gambosa

April

An unusually white fungus, found in the bluebell area of the oakwood.

Blusher

BlusherAmanita rubescens

June

Summer is not a generous season for toadstools. This one was found in a fairly open section of our beechwoods. It 'blushes' pink when bruised or cut.

BALL or CAP

Fungi in the form of a ball are usually puffballs of one sort or another. They can occur (not necessarily on our Reserve) at anything up to football size. Starting off as a solid mass of tissue, everything except the outer skin turns into a mass of millions or microscopic spores: they can escape either through a hole in the top or by the case splitting open. The 'puff' of such spores arises when a mature puffball is prodded, or even hit by a raindrop. Leopard earthball

Leopard earthballScleroderma areolatum

December

An easily overlooked element of the autumn beechwood floor.

Earthball

EarthballAnother species of Scleroderma

December

This one was in an area of mixed beech, oak and hawthorn woodland.

Common puffball

Common puffballLycoperdon perlatum

December

Individual specimens may have a visible stumpy stalk but the top is always more or less spherical.

Wolf's milk (!) :: Lycogala terrestre :: May :: Growing on old fallen timber in the oakwood area, they were thought to be unusually coloured young puffballs. But they turn out to be a slime mould (technically, not a fungus at all) which exists in two forms: it must be the other, slimy form that inspired the strange name. For further information about slime moulds see this article or more specifically this illustrated discussion.

Wolf's milk (!) :: Lycogala terrestre :: May :: Growing on old fallen timber in the oakwood area, they were thought to be unusually coloured young puffballs. But they turn out to be a slime mould (technically, not a fungus at all) which exists in two forms: it must be the other, slimy form that inspired the strange name. For further information about slime moulds see this article or more specifically this illustrated discussion.CUP

Scarlet elfcup :: Sarcoscypha austriaca :: February :: Colour distinguishes this fungus, despite its modest size and being half hidden in the twigs and leaves of the winter woodland floor.

Scarlet elfcup :: Sarcoscypha austriaca :: February :: Colour distinguishes this fungus, despite its modest size and being half hidden in the twigs and leaves of the winter woodland floor.SOFTSIDES

Lots of fungi are to be found sticking out of the sides of live trees, dead trees and fallen timber. Some are hard, long-lasting structures: those are further down the page, listed as Brackets. But this section shows softer structures, some of which last a few weeks while others may last longer but don't have the rigidity of the brackets. Because of the variability of life-span the time of year can be less significant. Oyster mushroom

Oyster mushroomPleurotus ostreatus

August

This summer eruption was on a long-dead beech beside the woodland path.

Branched oyster mushroom

Branched oyster mushroomPleurotus cornucopiae

August

Another long-fallen beech trunk close to the one above.

Sulphur polypore

Sulphur polyporeLaetiporus sulphureus

September

Growing on an old tree stump, almost certainly a beech.

Turkeytail fungus

Turkeytail fungusTrametes versicolour

Photographed in December

Growing on fallen timber, this growth persists during the year and might be considered a small bracket formation. Colours vary, but the outer edges are lightest.

Oyster fungi

Oyster fungiPleurotus species

December / January

A fungus-rich dead beech produced this display in midwinter. There is a normal view (left), an underneath view to show the gills, and a postscript (right) to show how the structure had collapsed just 21 days later.

Hairy stereum / Hairy curtain crust

Hairy stereum / Hairy curtain crustStereum hirsutum

Photographed in January

Old felled beech timber has been used by this fungus.

Velvet shank

Velvet shankFlammulina velutipes

January

These fruiting bodies appear in the winter months on dead wood. (This species is cultivated, mainly in Japan, and sold as 'Enoki', 'Enokitake' or 'Enoko-take'.)

Grass oysterling (?) :: Crepidotus species :: January :: The smallest of these soft brackets on dead twigs and timber, it is most likely to be C. epibryus.

Grass oysterling (?) :: Crepidotus species :: January :: The smallest of these soft brackets on dead twigs and timber, it is most likely to be C. epibryus.BRACKET

Fragrant Bracket

Fragrant BracketTrametes suaveolens

Photographed in March

An old decapitated beech trunk was host to these unusual almost-white bracket fungi, inconveniently high up. Apparently they smell of aniseed when cut or damaged, hence the 'fragrant' name. (The top one had some residual snow on it.)

Southern bracket fungus :: Ganoderma australe

Close to the start of the woodland walk is an old felled trunk, almost certainly of a beech, half-hidden by brambles. But the presence of three of these bracket fungi was noticed in January. All three can be seen in the middle picture which was taken in April to illustrate the profuse distribution (by air currents) of the brown microscopic spores. That process continued for months, as the third picture illustrates - admittedly after a perod of dry, calm weather - in June.

Blushing bracket fungus

Blushing bracket fungusDaedaleopsis confragosa

Photographed in October

Commonly occurring with several brackets on a single tree, look for these hard discus-shaped brackets on willows and alders, close to our watercourses. They are themselves tough and woody, persisting all year. The underneath view shows that the white surface has pores rather than gills.

Hoof fungus

Hoof fungusFomes fomentarius

Photographed in April

This is a provisional identification, it being unusual for the 'hooves' to overlap like this. Situated on an inaccessible very dead beech tree, it was not possible to obtain close-up pictures.

OTHER

Candlesnuff fungus

Candlesnuff fungusXylaria hypoxylon

November

This fungus was found on the woodland floor below some mature alders and poplars. It is a 'late rotter', being one of the last fungi to make use of already-rotten wood including modest twigs.

Orange jelly rot / Wrinkled crust

Orange jelly rot / Wrinkled crustPhlebia radiata

August

Another of the wide range of organisms that contribute to the rotting of wood. (Apparently the colour is merely creamy in the early stages.)

Jew's ear fungus

Jew's ear fungusAuricularia auricula-judae

November

A common brown fungus with variously-shaped stiff jelly-like components, which can persist for a few months.

Scrambled egg mould

Scrambled egg mouldFuligo septica

August

A bright splash of colour on the top of a very old beech stump was a type of 'slime mould' sometimes listed as 'Dog vomit mould'!

Coral spot fungus

Coral spot fungusNectria cinnabarina

January

A common fungus on dead wood, which may be seen at any season of the year.

Crystal or white brain fungus

Crystal or white brain fungusExidia:

E. nucleata

or perhaps

E. thuretiana

January, March

A strangely featureless jelly fungus, on dead wood in wintertime.

(No common name)

(No common name)Exidia plana

March

Another winter jelly fungus on old timber, beech in this case.

Yellow brain fungus

Yellow brain fungusTremella mesenterica

February

A more colourful winter jelly fungus, this one was on a small fallen oak branch.

Beech barkspot

Beech barkspotDiatrype disciformis

March

Hardly looking like a fungus at all, beech barkspot seems to be confined to dead beech timber. (Had the patches been shiny it would have been 'beech tarcrust' instead.)

This is manifestly not a mushroom! It is included here as it IS a wild fungus, possibly best thought of as a plant disease on a par with blackspot on roses and more seriously the Phytophthora infestans potato blight fungus that caused the nineteenth-century Irish famine and which still troubles potato growers, amateur and professional, to this day. This one could possibly be a kind of 'stem rust' affecting last year's brambles, conceivably Arthuriomyces peckianus or Gymnoconia nitens. The yellow dust is the spores of the fungus.

This is manifestly not a mushroom! It is included here as it IS a wild fungus, possibly best thought of as a plant disease on a par with blackspot on roses and more seriously the Phytophthora infestans potato blight fungus that caused the nineteenth-century Irish famine and which still troubles potato growers, amateur and professional, to this day. This one could possibly be a kind of 'stem rust' affecting last year's brambles, conceivably Arthuriomyces peckianus or Gymnoconia nitens. The yellow dust is the spores of the fungus.